How important is your chair?

Reading marketing materials for high-end office chairs can leave you with the belief that the ingenious, scientifically researched solutions used in their products guarantee a healthy spine. However, I have yet to meet a physical therapist or orthopedic surgeon who would place a great emphasis on chairs, let alone advise spending $1,000 on an upmarket chair. Professional recommendations for patients who have (or want to prevent) back problems are quite different, and generally focus on three things: sitting less, moving more and avoiding things that overload your spine. It is therefore safe to assume that replacing your average $100 office chair with a $1,000 ergonomic model will only be a small piece of the back health puzzle – perhaps no more than 10 percent of the whole. This is why I wrote an entire FAQ on preventing back problems. You should probably read it if you’re a computer worker and you’re worried about the remaining mileage you can get out of your back.

Rule Number One

Never buy a chair without trying it out first in your own workspace. I cannot stress this enough. The worst thing you can do is read a bunch of Amazon reviews and buy the chair that got the highest average rating, or the chair that all your friends are raving about. People have wildly differing bodies, working habits and preferences. I was made aware of this fact during a chair-testing marathon that I did together with two of my friends (B and P), who were also in the market for new office chairs:

- B and I loved the Steelcase Leap, while P immediately eliminated it because of the “sticky” backrest that doesn’t provide enough support as you lean forward.

- I found the Steelcase Please very comfortable, but I didn’t like the armrests; to B, it felt about as comfortable as a wooden plank, but he didn’t mind the armrests (which he doesn’t use anyway).

- P and I both loved the Steelcase Think, while B found that the plastic strings in the backrest dug into his back.

The second worst thing you can do is to buy a chair after testing in the store for 30 minutes, with no possibility of returning it. There are a number of reasons why it’s a bad idea:

- An in-store test won’t expose certain issues. You won’t find out that the armrests keep bumping against your desk because they don’t retract far enough. You won’t notice that the seat gets uncomfortably hot after 1 hour of sitting. You won’t pay attention to that slightly sticky knob. Issues like that can really ruin your long-term experience.

- An in-store test can also make you reject a chair prematurely. For example, if you’re testing a chair that feels harder than your current chair, it will initially seem uncomfortable, perhaps unacceptably so. But that impression can vanish after a day or two of sitting in the chair.

- I don’t know about you, but I don’t like having the salesman over my shoulder.

The solution is to order from a vendor with a good return policy, or from a store that will allow you to test chairs for a few days before buying. In the office furniture business, companies frequently test-drive chairs in their own offices before they make a purchase – if you’re an individual, you just have to convince your local dealer to extend the same practice to you.

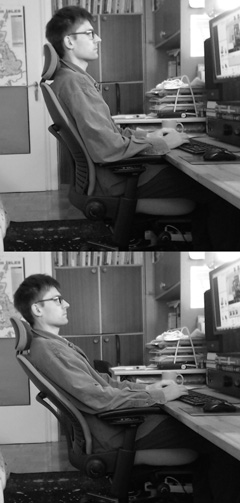

The virtues of changing your position

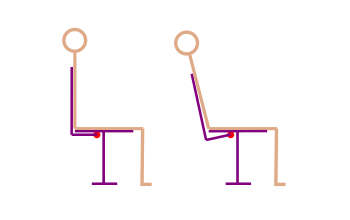

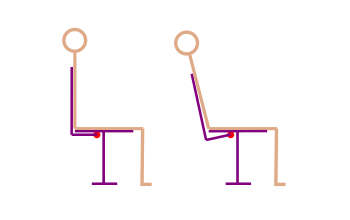

It is important to change your sitting position frequently. This allows you to spread the load among different sections of your spine, giving each section sufficient time to regenerate. At a minimum, your chair should enable easy switching between two positions:

- the “near-upright” position

- the “reclined” position

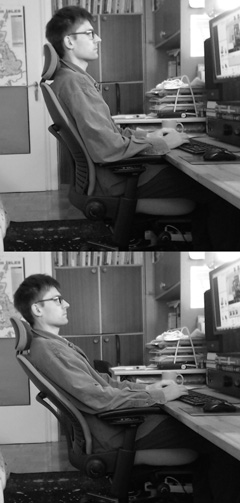

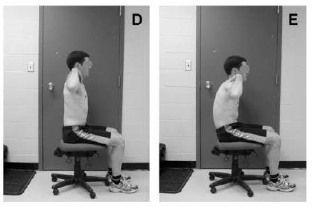

The near-upright position (~115°) vs. the reclined position (~130°)

The reclined position is a great way to take some load off your lumbar spine, which is the part of the spine that is the source of the vast majority of back pain episodes. Instead of having your spine bear the entire weight of your head and torso, you’re letting the backrest take some of the load. In addition, as you recline, you’re restoring the natural curvature of your lumbar spine. (See more discussion of the mechanics.)

Unfortunately, reclining also makes your neck muscles work harder to keep your head from dropping backwards. In addition, if you want to keep your gaze at screen level, you have to flex your cervical spine and stretch the muscles in the back of the neck. Finally, it is harder to type in this position. For these reasons, the reclined position is best used for short periods (say, less than 20 minutes) when you’re not typing a lot – for instance, when you’re thinking about what to write next, casually browsing the Web, or watching a short video. Your trunk in the reclined position should be at around 130°.

A headrest allows you to maintain the reclined position longer, but in my experience, the depth of the headrest has to be adjusted very precisely. Otherwise, your head will either drop too far back or stick forward – either situation results in a sore neck. Unfortunately, chairs with good, highly adjustable headrests are few and far between. Furthermore, although a good headrest will take some (but not all) load off your muscles, it won’t change the fact that your cervical spine is constantly flexed (so you can see the screen), putting pressure on your intervertebral discs and stretching the muscles that straighten your neck.

The near-upright position is much easier on your neck at the expense of your lumbar spine. Your trunk should be somewhere between 100° and 120° – I personally prefer to get closer to 120°. Of course, you can and should continually change this angle if your chair allows it. Wider angles transfer more stress from the lumbar region to your neck.

Types of recline mechanisms

Before we go any further, I should explain some terms that I will be using in this post. There are two major types of recline mechanisms in task chairs:

- Smooth. This is the type you are probably most familiar with. It is found in your average low-end chair, as well as most high-end ones not made by Steelcase. If you put a little more weight on the backrest, it will recline. The further you recline, the more the backrest will resist your weight, which sets a “soft limit” on how far you can go. (Depending on the chair, resistance can rise slowly or quickly – if it rises slowly, you can recline further, but you also feel less stable.)

- Sticky. This is used in most Steelcase chairs. With the smooth mechanism described above, the backrest reacts to your every movement – just putting your arms forward will often result in it tilting forward. With the sticky mechanism, the experience is quite different. As you push back, the backrest does not immediately recline – instead, it stays in place, as if it were a little stuck, until you apply enough force to overcome the static friction. Once it starts moving, you can easily put it at any angle you wish, as the backrest does not respond with increasing force – the resistance is practically the same across the whole range of motion, allowing you to put the back in any position you wish. In this sort of chair, what keeps you from dropping all the way back is not the spring-like resistance – it’s the static friction.

Here is a clip demonstrating a smooth mechanism on a Sedus Open Up chair. Notice that the backrest remains glued to my back, responding to my every move. Just bringing my arms closer to my body is enough to shift the balance and increase the recline angle. When I put my hands behind my head, my center of gravity shifts even more, resulting in a very large recline. The range of movement is limited by the increasing counterforce of the backrest – I cannot maintain a large recline without putting my arms behind me. To do so, I would have to use my muscles (until they got tired) or change the tension setting (which is a bit of a hassle).

And here’s a clip showing the sticky mechanism on the Steelcase Leap. Notice that small movements are ignored. When I move my arms around, the backrest flexes a bit, but the recline angle stays the same, held in place by static friction. In order to change the angle, I would have to do overcome the initial friction with my abdominal or back muscles. Once I do this initial work, my range of motion is unlimited. I can take any position (no matter how reclined) and maintain it without effort.

Recline mechanisms can also be classified along another dimension, which is independent of the smooth–sticky dimension:

- Backrests with a tension control. The chair has a knob that lets you adjust the resistance of the backrest according to your weight and your preferred recline angle, with heavier users requiring more resistance. This is by far the most common type.

- Backrests with a weight mechanism. The resistance is automatically determined by your weight (the seat is connected to the recline mechanism). The idea is that users of different weights can sit on the chair, and the chair will automatically adjust the backrest resistance, so that they can all sit in roughly the same “optimal” position. This is especially handy in work environments in which one chair gets used by many different people. Example chairs that use this type of mechanism are the Humanscale Liberty and the Steelcase Think.

Easy changing between at least two positions

For reasons explained two sections earlier, you need a chair that, at a minimum, enables you to easily switch between two positions: the near-upright position and the reclined position. Of course, to do that, a chair must offer a properly reclined position (around 130°) in the first place.

Generally speaking, smooth backrests have difficulty with easy position switching. If you set the backrest for the near-upright position, then you cannot recline very far. The reason is that the resistance will go up quickly. You can use your muscles to force a reclined position, but this takes a lot of work and is impossible to maintain for any significant amount of time. You can make it a bit easier by putting your hands behind you, but then you cannot operate the keyboard and mouse, so the reclined position ends up being limited to passive activities like movie-watching.

The proper way to recline would be to turn the tension knob and lower the backrest resistance. Now you can recline easily, but you’ve traded away the near-upright position! If you try to sit upright, you will find that the backrest does not provide adequate support, so you have to use your abs or you drop back. Exaggerating a little, a smooth backrest mechanism only offers one position for a given resistance setting. Of course, the backrest is highly mobile and you can rock back and forth around some center point – just not very far and not for very long.

In the case of “smooth” chairs with a weight mechanism instead of adjustable resistance, your options are even more limited. On a standard chair, you can at least change your position by turning the tension control knob – with a weight mechanism, your position is determined by your weight. The chair’s designers picked a recline angle that they considered optimal, and the weight mechanism is supposed to ensure that every user sits at this angle, regardless of their body weight. If an adjustable-tension chair only allows one position for any given resistance setting, a chair with weight-based resistance only allows one position – the one selected by the chair’s designer. There are exceptions to this rule – for instance, the Steelcase Think chair has a weight mechanism with an additional, easy-to-reach knob that lets you choose between “weight-based resistance” and “weight +20%”, thus satisfying the requirement of enabling easy position changes (though not without some mechanical shortcomings).

Let’s go back to chairs with adjustable resistance. As I mentioned above, you can switch between a near-upright position and a reclined position by turning the resistance knob. However, this doesn’t work in practice, because tension controls on chairs are continuous. Imagine you’ve just spent 5 minutes fiddling with the knob to get your preferred upright position. After working for a while, let’s say you want to watch a cat video – a perfect opportunity to give your back a bit of rest. In order to recline, you turn the knob a few times to lower the resistance. Big mistake. You see, there is no back button that lets you just go back to your previous backrest resistance. When you’re done watching that video, you’re going to have to painstakingly recreate the original position of the knob with no visual or tactile cues to guide you. Try it once, you’ll never do it again. Even putting that aside, the fact that you typically have to turn the resistance knob several times to go from a near-upright to a reclined position will surely dampen your enthusiasm for healthy position changes.

There are chairs with discrete resistance controls, but I haven’t seen one where the number of steps would be smaller than 7. This means that you’ll have to turn the knob through a few “clicks” before you go from upright to reclined. Turning a knob 3 steps left every time you want to recline, and then 3 steps right when you want to be upright again, while dramatically better than the continuous option, is still not the height of convenience. A good chair should make it super-easy to change positions; otherwise, the user will just avoid the hassle and work in the same position for hours, which is a complete ergonomic disaster.

Well, what about locks and tilt limiters? Don’t they help? Let’s define our terms first. A lock freezes the backrest so that it can move neither forward nor back; typically, this is enabled by pushing the backrest into the desired angle and then engaging some kind of lever. A tilt limiter is a hard limit on the backward movement – the backrest can still move forward; typically, you select one of a few angles using a lever or knob. These mechanisms have some problems, most of which are not inherent, but rather the result of the way they are typically implemented:

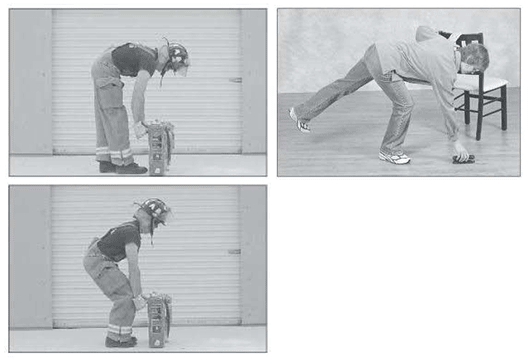

- The lock/limiter control often isn’t terribly easy to reach. This is a real problem because it discourages you from changing your position.

- It may be necessary to perform some extra gymnastics before the chair will allow you to disengage a tilt limiter or a lock. For example, on the Aeron, you have to bend forward (see video example). Other chairs may have other mechanical constraints.

- If you set your backrest to a low resistance and rely on a lock/limiter to stay upright, it will be hard to go from a reclined to an upright position. The backrest won’t provide a lot of forward force, so you’ll have to work your abs (compressing your spine in the process).

- If you set your backrest to a high resistance and rely on a lock to stay reclined, you will have to use a lot of force to effect a recline that you can lock into (again compressing your spine).

- If the backrest does not have a lot of inherent flexibility, a tilt limiter or lock can freeze your back in one position without the possibility of micromovements (which is suboptimal for reasons detailed below). Hitting a tilt limit can also feel unpleasant (here’s a video example).

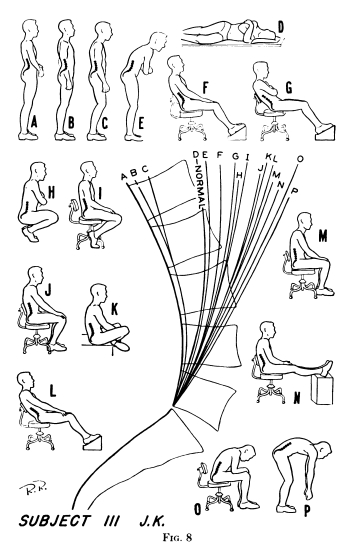

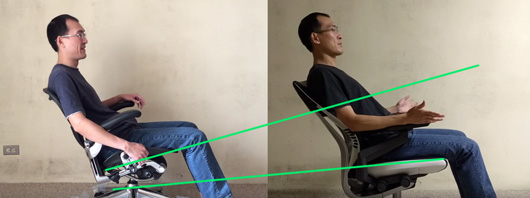

Large hip angle

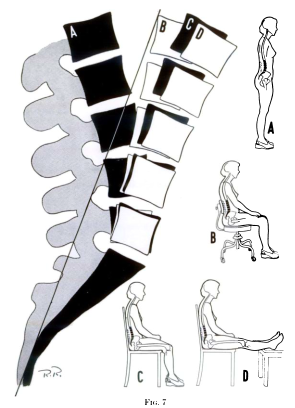

When you’re sittting upright, your lumbar spine is actually bent, putting backwards pressure on your intervertebral discs. The degree of flexion depends on the angle between your thighs and your trunk (the hip angle). Your spine is in a neutral position when the hip angle is 135°.

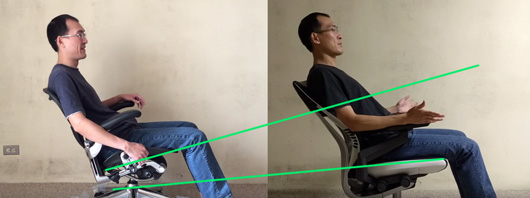

Therefore, it is good to have a chair that opens up your hip angle as you recline. The fact that a chair has a good recline angle does not mean that it opens up your hip angle. For example, in the Herman Miller Aeron chair, the seat tilts back almost at the same rate as the backrest – if you recline by 10°, the seatpan will also tilt back by something close to 10°. This means that, at maximum recline, the hip angle is only a bit larger than in the upright position! Reclining on the Aeron is still beneficial, because you’re transferring load from your spine to the backrest – but it’s not as beneficial as it could be if the chair also let you un-flex your lumbar spine.

The seat on the Aeron chair (left) tilts back together with the backrest – as a result, the hip angle is only 115° in the maximally reclined position. By contrast, the seat on the Steelcase Gesture (right) tilts only slightly, allowing a very open hip angle of 135°. Source: bkwtang’s reviews of the Aeron and Gesture.

Micromovements (“rockability”)

It’s a good idea to pick a chair which allows you to rock back and forth around your chosen backrest position. Small movements are gentle exercise for your core muscles; they also improve your circulation, delivering more oxygen into the brain – though obviously they cannot replace standing up and walking around, for example.

The nice thing about chairs with smooth backrest mechanisms is that they give you micromovements “for free” (except when you’re using a lock or a tilt limiter). Here’s an example clip from an online video on the Herman Miller Embody:

Chairs with sticky backrests, by nature, are not very good in the micromovements department. The backrest maintains its recline angle until you exert significant force. However, many chairs of this type have flexible backrests which permit limited back-and-forth motion. Here’s a Steelcase Leap, which is pretty good for a sticky chair:

This is definitely less fun and less healthy than rocking with a smooth backrest, but it’s better than nothing.

Sticky or smooth backrest – a recap

I’ve said a lot of different things about sticky and smooth backrests, so let’s recap the unique strengths of each backrest type:

- A smooth backrest gives you rockability (but only in one position, because you’ll probably want to use the tilt lock/limiter to stay upright, which makes it impossible to rock)

- A sticky backrest gives you easier switching between positions (you don’t have to mess with any knobs or levers) and allows you to pick any position (not just one of the pre-defined positions)

From a spine health perspective, easy position switching is probably more important than micromovements – therefore, speaking in the abstract, chairs with sticky reclining mechanisms have an advantage. In practice, however, it all comes down to the particular implementation: how fiddly is the tilt limiter? how much micromovement does a sticky backrest allow? how “sticky” is it? etc.

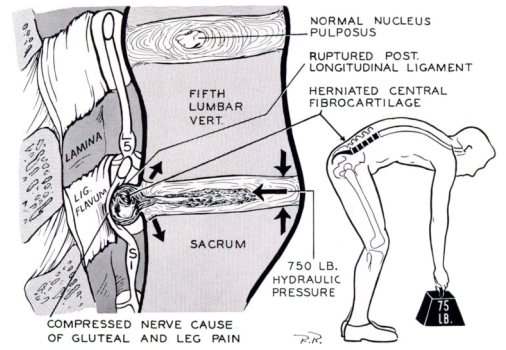

Lumbar support

As discussed above, when you’re sitting upright, your lumbar spine is flexed. This flexion pushes your intervertebral discs backwards, where they can eventually bulge out and press on your nerves. The best way to un-flex your lumbar spine is to stop sitting in an upright or near-upright position – unfortunately, this kind of position is more or less necessary for intensive computer work. There is, however, a way to mitigate the problem – a chair with a lumbar support will reduce lumbar flexion in the upright position.

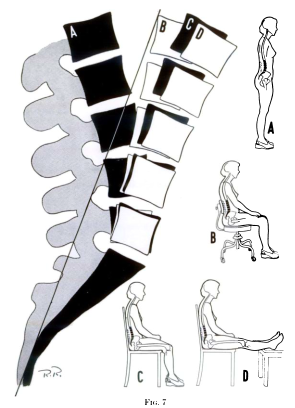

Here is a figure from Jay Keegan’s classic 1953 paper. Note that going from a basic chair (C) to a chair with lumbar support (B) brings you closer to a neutral position. (The neutral position is not pictured, but it’s about halfway between A and B.) The difference is not enormous, but it’s not insignificant, either.

Therefore, an ergonomic backrest should be shaped in a way which fills your lumbar curve. There are two dimensions to this. First, the depth of the lumbar support should be sufficient (and preferably adjustable) – generally as deep as possible without causing discomfort over longer sitting sessions. It’s better to err on the side of more prominent support, because the health consequences of “slouching” your lumbar spine are more serious than those of maintaining an excessive curve. The vast majority of office chairs advertised as “ergonomic” do not offer lumbar support of sufficient depth.

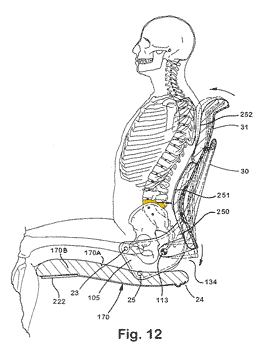

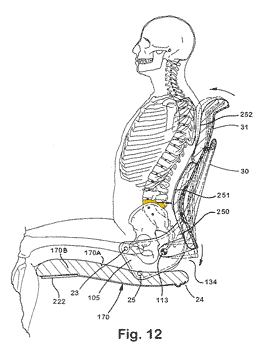

Model seated on a Steelcase Leap prototype. The apex of the lumbar support aligns with the 4th lumbar vertebra (marked in yellow). The bottommost lumbar vertebra is hidden behind the pelvis. (adapted from this Steelcase patent)

The second dimension is the height. The critical area which needs to be supported is the lowest two lumbar vertebra, because that’s where 95% of all spinal herniations occur. To locate it, reach to your back and feel the top edge of your pelvis (posterior iliac crest). You can also try to feel the first vertebra that comes out of your sacrum (it’s easier to do this when bending over). If the lumbar support is too high, it can leave a gap and allow the lowest two lumbar vertebra to flex. As a rule of thumb, I would disqualify any chair in which the apex (most protruding part) of the lumbar support is more than 20 cm (8 inches) above the seatpan.

Many chairs have height-adjustable lumbar supports. This is generally a good idea, because people’s spines come in different heights. However, lack of vertical adjustability is not a dealbreaker. It is possible to design a chair that has a fixed lumbar support at a height that works for most users.

In most chairs, a “lumbar gap” appears between your lower back and the backrest as you recline. This is caused by the fact that the backrest doesn’t rotate around the point where your back rotates (which is close to the point where the backrest meets the seat). It rotates where the mechanism is located, which is somewhere under the seat. This difference in centers of rotation means that the lower part of the backrest has to move further and further away from the seat as you recline. This means that your lower back has less and less support. Here’s a quick visual explanation:

The backrest, rotating around a point under the seat (red dot), moves away from the seat and no longer supports the user’s lower back.

Some chairs, like the Humanscale Liberty or Steelcase Please, have a special construction that eliminates this, and on the better chairs, this will be not so much a “gap”, but a gradual loss of support (I think it depends on the center of rotation, and possibly on other mechanical considerations, as well as the adaptability of the backrest).

While good lumbar support across the whole range of recline can significantly increase your comfort level, I do not think it is a serious problem for spine health if a chair doesn’t have it. Although in the upright position your lumbar area should always be supported to prevent flexing that part of the spine more than it needs to be flexed, in the reclined position this is less important for two reasons: (1) the weight borne by the lumbar spine is much smaller (the backrest bears a large part of it), and so the pressure on intervertebral discs will be smaller as well, and (2) your lumbar curve automatically deepens in the reclined position, so slouching becomes harder. (I imagine a lumbar gap could be a problem for back patients who are sensitive to motion in that part of the spine.)

Backrest flexibility

People have very different backs. What’s more, each person’s back changes its shape depending on the recline angle (the spine does not work as a single unit). That is why any ergonomic chair worth its salt must have a backrest that adapts to your back. The two most common implementations are flexible plastic backrests (Leap, Gesture) and mesh backrests (Humanscale Liberty, Herman Miller Aeron). Both can work very well, with the mesh backrests having the added advantage of much better airflow.

Some chairs also have a knob that increases or decreases the curviness of the backrest, as in the Leap and Embody. This is good (more adjustments is always better in my book), but not essential.

Seatpan

The seat pan should not come up to your knees. A seat pan that’s too short is better than one that’s too long. A too-long seatpan will make it harder to move your legs (remember, it’s healthy to change position) and to get out of the chair. It is just not very comfortable. A short seatpan will be fine because people sit on their butts, not on their thighs.

According to conventional ergonomic wisdom, the seat pan should tilt back a little when you recline. When you push your back against the backrest, your butt will go up. A tilted seatpan stops it from sliding forward. I don’t think it’s a big deal if the seatpan doesn’t tilt (Humanscale Liberty) or tilts in an almost imperceptible way (Steelcase Leap, Think) – but then I would recommend choosing a high-friction fabric to prevent slipping. For reasons described in the hip angle section, the seatpan should not tilt too much – otherwise, it will prevent you from opening up the angle between your legs and torso. Another issue is that when the seat tilts, your butt will drop down with respect to your desk, which can make it harder to use the keyboard and screen.

Be careful with chairs that have adjustable seatpans. On some models, it is possible to slide the seatpan forward so far that you can no longer comfortably sit with your butt all the way back because you end up falling into a “hole”.

Armrests

The way I see it, armrests on an office chair achieve two things:

- They take some load off your spine. Your arms weigh something like 5 kg. I’m not sure if your spine will notice the difference, since it normally bears more than 50 kg (the weight of your head and torso), but multiply it by 40 years of sitting and it could add up.

- They increase your precision when using the mouse. When your forearm is resting on something, you can move the mouse pointer more accurately. This is most apparent when playing reflex-based games (first-person shooters, real-time strategy games).

On the other hand, armrests can have serious disadvantages. The most important one is that hard, poorly adjustable armrests can cause permanent disability. I have actually met a guy who permanently damaged the ulnar nerve in his arms by resting his elbows on armrests – now his hand movement is impaired and he’s officially disabled. If you’re going to use armrests, make sure they’re soft. Be sure to adjust them so that there’s no pressure on your ulnar nerve (the same nerve that causes the “funny bone” effect). It’s also probably good if they are sloped toward the back, so that the bulk of the weight is on your forearms, rather than your elbows.

Armrest Fail. If you recline on some chairs, the armrests will take your hands away from your desk. (Source: bkwtang’s video review of the Aeron)

When you recline, the armrests should stay relatively level. If they tilt together with the backrest, they will tear your hands away from your desk (see picture on the right). A small amount of armrest tilt is acceptable – if the armrests are soft, you may still be able to keep your hands on your desk fairly comfortably. In fact, I only know two chairs in which the armrests stay totally level, regardless of the angle of recline – the Steelcase Leap and Steelcase Think.

There’s also the issue of personal preferences. In my experience, there are two kinds of people: those who like armrests and those who don’t. If you are in the latter group, you could consider yourself lucky. It’s much easier to find a good chair if you don’t care about armrests.

In general, my opinion on armrests is that if you’re going to use them, they have got to be very good armrests. Here’s what this means:

- must be soft (prevents ulnar nerve injury)

- not too much friction (otherwise, it’s hard to move your mouse while resting your forearms on them)

- they cannot prevent you from pulling up your chair as close to your desk as you like (i.e. avoid long armrests that don’t slide backward far enough) – otherwise, you may be inclined to leave a gap between your back and the backrest to compensate, which encourages slouching

- it must be possible to adjust them inward so that you can comfortably rest your forearms on them while keeping your fingers on the “home row” when touch typing (this eliminates at least of 50% of armrests – most are too wide)

- when you recline, they should stay relatively level

- fine-grained height adjustment, so that you can position them just below your desk level (your arms have to be supported, but you should also be able to easily take your forearms off them if you need to make large movements)

It’s pretty hard to find armrests that meet all of these requirements. The armrests on the Herman Miller Aeron tilt as you recline, tearing your hands away from your desk. The Embody‘s are too long and won’t let you sit close to your desk. Even the Steelcase Gesture, with the most adjustable armrests on the market, isn’t perfect – the rubbery material has too much friction. The only armrests that have no real weaknesses are the “4-D” Steelcase armrests found on the Leap, Amia and Think (the Think version is a bit harder and doesn’t have as much in/out adjustability, so it’s a bit worse). If you don’t like those armrests, you don’t like armrests, period.

Recap (the Tom Test)

Here’s a checklist of features that a good chair should have:

- Easy changing between at least two positions (near-upright and reclined)

- Open hip angle in the reclined position (at least 125°)

- Micromovements (rockability)

- Lumbar support

- Seatpan must not be too long

- Backrest should adapt to your back

- Armrests (if you care about them) – see Armrests

- No annoyances (poor thermals, fiddly controls, hard edges, etc.)

And I hope you haven’t forgotten Rule Number One: Never buy a chair without trying it out first in your own workspace!

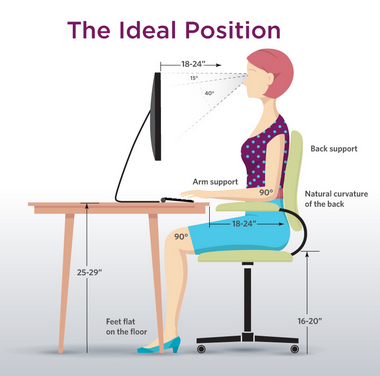

How to sit on your ergonomic chair?

See my back health FAQ, especially this question.

Chair reviews

In this series of blog posts, I will be posting short reviews of popular ergonomic chairs that I’ve had the opportunity to try out in my workspace. Stay tuned!