Policy no. 8 in the Terms of Service of the respected audiophile community Hydrogenaudio states:

8. All members that put forth a statement concerning subjective sound quality, must — to the best of their ability — provide objective support for their claims. Acceptable means of support are double blind listening tests (ABX or ABC/HR) demonstrating that the member can discern a difference perceptually, together with a test sample to allow others to reproduce their findings.

What a breath of fresh air. Other audio forums are full of snake-oil-peddling and Kool-Aid-drinking evangelists who go on and on about how replacing $200 speaker wires with $400 speaker wires “really opened up the soundstage and made the upper-midrange come alive”. The people at Hydrogenaudio know that such claims demand proper scientific evidence. How nice to see that they dismiss subjective nonsense and rely instead on the ultimate authority of ABX tests, which really tell us what makes a difference and what doesn’t.

Except that ABX tests don’t measure what really matters to us. ABX tests tell us whether we can hear a difference between A and B. What we really want to know, however, is whether A is as good as B.

1.

“Wait a second!”, I hear you exclaim. “Surely if I cannot tell A from B, then for all intents and purposes, A is as good as B and vice versa. If you can’t see the difference, why pay more?”

Actually, there could be tons of reasons. To take a somewhat contrived example, suppose I magically replaced the body of your car with one that were less resistant to corrosion, leaving all the other features of your vehicle intact. Looking at the car and driving it, you would not notice any difference. Even if I gave you a chance to choose between your original car and the doctored one, they would seem identical to you and you could choose either of them. However, if you were to choose the one I tampered with, five years later your vehicle’s body would be covered in spots of rust.

The obvious lesson here is that “not seeing a difference” does not guarantee that A is as good as B. Choosing one thing over another can have consequences that are hard to detect in a test because they are delayed, subtle, or so odd-ball that no one even thinks to record them during the test.

But how is this relevant to listening tests? Assuming that music affects us through our hearing, how could we be affected by differences that we cannot hear?

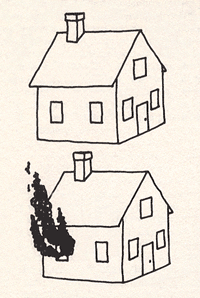

In his fascinating book Burning House: Unlocking the Mysteries of the Brain, Jay Ingram describes the case of a 49-year-old woman suffering from a condition called hemispatial neglect (the case was researched by neuropsychologists John Marshall and Peter Halligan). Patients with hemispatial neglect are unable to perceive one (usually the left) side of the objects they see. When asked to copy drawings, they draw only one side; when reading out words, they read them only in half (e.g. they read simile as mile).

In Marshall and Halligan’s experiment, the woman was given two simple drawings showing two houses. In one of the drawings, the left side of the house was covered in flames and smoke; the houses looked the same otherwise. Since the flames were located on the left side, the patient was unable to see them and claimed to see no difference between the drawings. When Marshall and Halligan asked her which of the houses she would rather live in, she replied — rather unsurprisingly — that it was a silly question, given that the houses were identical.

In Marshall and Halligan’s experiment, the woman was given two simple drawings showing two houses. In one of the drawings, the left side of the house was covered in flames and smoke; the houses looked the same otherwise. Since the flames were located on the left side, the patient was unable to see them and claimed to see no difference between the drawings. When Marshall and Halligan asked her which of the houses she would rather live in, she replied — rather unsurprisingly — that it was a silly question, given that the houses were identical.

However, when the experimenters persuaded her to make a choice anyway, she picked the flameless house 14 out of 17 times, all the time insisting that both houses look the same.

Marshall and Halligan’s experiment shows (as do other well-known psychological experiments, including those pertaining to subliminal messages) that it is possible for information to be in a part of the brain where it is inaccessible to conscious processes. This information can influence one’s state of mind and even take part in decision-making processes without one realizing it.

If people can be affected by information that they don’t even know is there, then who says they cannot be affected by inaudible differences between an MP3 and a CD? Failing an ABX test tells you that you are unable to consciously tell the difference between two music samples. It does not mean that the information isn’t in your brain somewhere — it just means that your conscious processes cannot access it.

So the fact that you cannot tell the difference between an MP3 and a CD in an ABX test does not mean that an MP3 is as good as a CD. Who knows? Maybe listening to MP3s causes more fatigue in the long run. Maybe it makes you get bored with your music more quickly. Or maybe the opposite is true and MP3s are actually better. We can formulate and test all sorts of plausible hypotheses — the point is, an ABX test which shows no audible difference is not the end of the discussion.

2.

I have shown that the lack of audible differences between A and B in an ABX test does not imply that A is as good as B. Before you read this post as an apology for lossless audio formats, here is a statement that will surely upset hard-core audiophiles:

The fact that you can tell the difference between an MP3 and a CD in an ABX test does not mean that the MP3 is worse than a CD.

First of all, the differences between MP3s encoded at mainstream bitrates (128 kbps and 192 kbps) and original recordings are really subtle and can be detected only under special conditions (quiet environment, good equipment, full listener concentration, direct comparisons of short samples). Because the differences are so tiny, we cannot automatically assume that it is the uncompressed version that sounds better. Subtle compression artifacts such as slightly reduced sharpness of attacks on short, loud sounds may in fact be preferred by some listeners in a direct comparison.

Secondly, even if we found that the uncompressed version is preferred by listeners, that wouldn’t necessarily mean that it is better. People prefer sitting in front of the TV to exercising, but the latter might make them feel much better overall. If it were discovered, for example, that compressed music is less tiring to listen to (this is of course pure speculation), then that fact might outweigh any preference for uncompressed sound in blind tests.

Summary

The relevance of ABX tests to the lives of music lovers is questionable. Neither does the absence of audible differences imply equal quality, nor does the presence of audible differences imply that the compressed version is inferior. Rather than being the argument to end all debate, the results of ABX tests are just one data point and the relative strengths of various audio formats may well be put in a new light by further research.

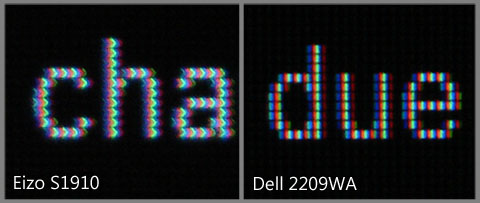

After years of using the excellent Eizo S1910 19″ display, I finally decided to look for a bigger, wider screen that would work better for watching movies and gaming while retaining the top-notch image quality of my current display. My needs are admittedly diverse: I work with text (whether I’m writing, coding or translating), I edit photographs in Photoshop and design Web pages, I watch movies, and I play games (non-competitively).

After years of using the excellent Eizo S1910 19″ display, I finally decided to look for a bigger, wider screen that would work better for watching movies and gaming while retaining the top-notch image quality of my current display. My needs are admittedly diverse: I work with text (whether I’m writing, coding or translating), I edit photographs in Photoshop and design Web pages, I watch movies, and I play games (non-competitively).